It could be argued that Frederick County saved the Union more than once during the Civil War. It was here that General Robert E. Lee’s “lost orders” were found, giving the Union Army the opportunity to stop the Confederate Army’s first invasion of the North at Antietam. It was also here that the Battle of Monocacy was fought to thwart the Confederate Army’s last invasion of the North.

It could be argued that Frederick County saved the Union more than once during the Civil War. It was here that General Robert E. Lee’s “lost orders” were found, giving the Union Army the opportunity to stop the Confederate Army’s first invasion of the North at Antietam. It was also here that the Battle of Monocacy was fought to thwart the Confederate Army’s last invasion of the North.

The Battle of Monocacy

By the summer of 1864, the tides of war had turned against the Confederate States. General Lee had been forced to pull back his troops to protect Richmond and Petersburg in Virginia Anxious to press his attack on the Southern cities, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant shifted idle troops from the defensive ring of 65 forts around Washington D.C. to aid in his attack. This left the capital city lightly defended.

“The forts were left poorly manned with third tier soldiers,” said Jack Sheriff, president of the Frederick County Civil War Roundtable. “They were invalids, one-armed soldiers or poorly trained, but they did have a lot of ammunition and guns.”

Lee sent Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and 15,000 troops to the west to secure the Shenandoah Valley, but then to move north and invade Maryland. Early wanted to use his men to threaten or even capture Washington. It was hoped that such an act would erode support for the war in an election year and relieve pressure on Richmond and Petersburg.

“Morale in the north for the war was low. To have the capital taken would have been a huge blow,” Park Ranger Tracy Evans.

Early and his men arrived in Harpers Ferry on July 4. They crossed the Potomac River near Sharpsburg, and then moved east to Frederick and south toward Washington. A railroad telegrapher saw the troops and sent word to John Garrett, president of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, who in turn, sent word to Major Gen. Lew Wallace in Baltimore.

As Early’s men moved through Maryland, they ransomed Hagerstown for $20,000, Middletown for $5,000 and Frederick for $200,000.

“Sen. (Charles) Mac Mathias tried every year to get the government to pay back the money, but it never happened,” said Sheriff.

Efforts to have Frederick reimbursed all of the money it lost date back to 1879. Mathias not only wanted the $200,000 repaid but that amount with four-percent interest compounded since 1864.

Meanwhile, in Baltimore Wallace assembled 3,200 raw soldiers and headed to Monocacy Junction. He was unsure as to whether Early would be heading toward Washington or Baltimore and Monocacy Junction placed Wallace in a good position to intercept the Confederate troops either way.

Wallace knew his small army would be outnumbered. His goal was to delay Early and allow whichever city Early was heading toward time to reinforce their defenses.

On July 9, 3,400 additional troops arrived sent by General Grant. Though this more than doubled Wallace’s men, it still left them outnumbered more than two to one.

The Confederate forces began the battle with an attack on the bridges, which the Union was defending. The two armies fought throughout the day and when Wallace realized he could no longer hold his position, he fell back toward Baltimore leaving 1,300 men behind as casualties.

Early rested his troops that night. The next morning, the Confederate troops headed toward Washington. On July 12, they engaged the troops at Fort Stevens. These were no longer third-tier troops.

“The Battle of Monocacy had stopped the Confederate soldiers for one whole day and that gave Grant time to bring up reinforcements from Petersburg,” Sheriff said. “There’s no way the Confederates had enough men to break through.”

Although the Confederate Army had won their only victory in the north at Monocacy, it was a strategic defeat. Realizing that he wouldn’t be able to enter Washington, General Early took his troops back into Virginia under the cover of darkness on July 12.

“Someone coined the term the battle that saved Washington. It allowed time to get reinforcements into the capital,” Evans said.

Sheriff said that if Early had been able to win his way through the ring of forts and attack Washington, the Confederate Army might have been able to cause some trouble but it couldn’t have held the city.

“They could probably have burned buildings, captured supplies and raided the Treasury, but they would have had to leave because Grant’s men were coming,” Sheriff said.

Overall, the Battle of Monocacy was a small battle involving about 20,000 troops. As such, it tends to get lost among the surrounding and larger battlefields of Gettysburg, Antietam and Manassas.

For More Information

- Monocacy National Battlefield: www.nps.gov/mono

- The Official Records of the Battle of Monocacy: www.civilwarhome.com/Monocacy.htm

- Civil War Trust Battle of Monocacy Page: www.civilwarhome.com/Monocacy.htm

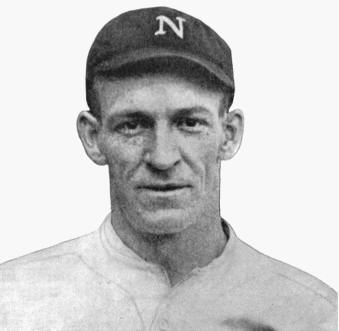

Author’s Note: The following is an article I wrote 10 years ago for The Dispatch newspapers. I’ve reprinted it with a few tweaks and added an update at the end. When I originally wrote this, no one knew what had happened to Tolbert Dalton. I wish I could take credit for solving this mystery, but it was the work of members of the Society for American Baseball Research. I wanted to bring closure to what was a 64-year-old mystery.

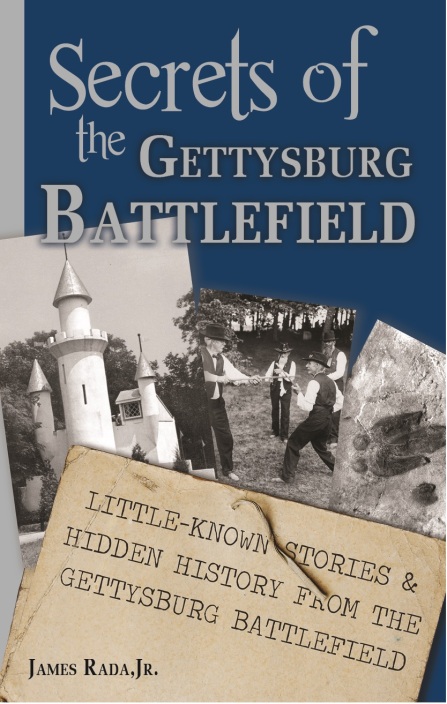

Author’s Note: The following is an article I wrote 10 years ago for The Dispatch newspapers. I’ve reprinted it with a few tweaks and added an update at the end. When I originally wrote this, no one knew what had happened to Tolbert Dalton. I wish I could take credit for solving this mystery, but it was the work of members of the Society for American Baseball Research. I wanted to bring closure to what was a 64-year-old mystery. Introducing the cover of my next book, Secrets of the Gettysburg Battlefield: Little-Known Stories & Hidden History From the Civil War Battlefield. It may still get a few tweaks, but I would say this is 95 percent there. The book will be available near the end of this month, but I was excited to show you the cover.

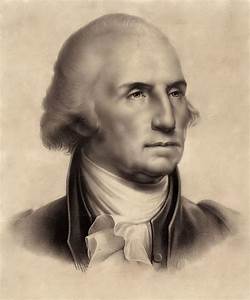

Introducing the cover of my next book, Secrets of the Gettysburg Battlefield: Little-Known Stories & Hidden History From the Civil War Battlefield. It may still get a few tweaks, but I would say this is 95 percent there. The book will be available near the end of this month, but I was excited to show you the cover. He might not have been able to tell a lie, but he could steal a library book.

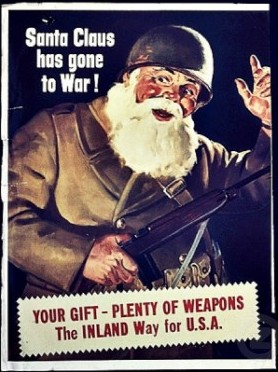

He might not have been able to tell a lie, but he could steal a library book. The “date which will live in infamy” cast a large, dark shadow over Christmas 1941 in Allegany County.

The “date which will live in infamy” cast a large, dark shadow over Christmas 1941 in Allegany County.