Help had arrived at Shallmar, Md. Trucks began arriving daily, braving the steep, narrow roads to reach the isolated coal town. A Baltimore meat packing company sent a load of fresh beef. The Maryland Jewish War Veterans collected toys. The Amici Corporation in Baltimore sent $50 to the Oakland Chamber of Commerce to purchase candy for the children of Shallmar. Plus, Amici employees raised another $1,000 for the town in general.

Help had arrived at Shallmar, Md. Trucks began arriving daily, braving the steep, narrow roads to reach the isolated coal town. A Baltimore meat packing company sent a load of fresh beef. The Maryland Jewish War Veterans collected toys. The Amici Corporation in Baltimore sent $50 to the Oakland Chamber of Commerce to purchase candy for the children of Shallmar. Plus, Amici employees raised another $1,000 for the town in general.

The Baltimore American Legion collected so much food and clothing that it filled a room at the War Memorial Building. Among the donated items was 300 pounds of bacon, 250 loaves of bread, 200 quarts of milk, cases upon cases of canned goods and groceries, 100 pairs of shoes, 20 men’s overcoats, 12 women’s fur coats and blankets, not to mention toys for the children.

From New York City, the Save the Children Federation said that it would be sending toys and other needed things to the town. The Cumberland local of the United Brewery Workers of America also began raised money. Cumberland dairies donated milk and bakeries donated bread.

Shallmar even made international news when the London Times interviewed Andrick for a story. Letters arrived from other European cities like Paris with words of concern for Shallmar’s residents.

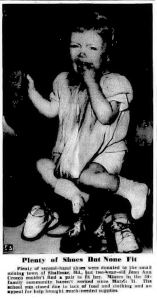

A photographer took a shot of two-year-old Jean Ann Crosco sitting amid a pile of shoes being distributed. She was crying because none of them fit her. Numerous newspapers all around the world ran the picture and donations poured in specifically for Jean Ann. About a week after the photo was published, Jean Ann’s mother told The Iola Register, “We have heard from every state in just a week. The kind people sent her dresses and other pretties. And she had about $200 in money gifts. And Jean Ann has forty—yes, forty—pairs of shoes.”

The picture spurred A. K. Rieger, president of Gunther Brewing Company in Baltimore, to buy all of the children in Shallmar a new pair of shoes.

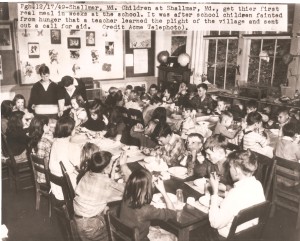

On Dec. 21, the senior class at a Cumberland Catholic girls’ school, cancelled its own Christmas party to throw one for the children of Shallmar in the school. Two days later, the United Paper Workers Union Local 67 came to town to throw the children another party.

The Cumberland Optimist Club alone had delivered more than 15 tons of food and clothing to the town by the middle of December and it was only one organization of dozens that was delivering food.

As Christmas Day approached, the downstairs of the J. Paul Andrick home filled with boxes and bags of letters and postcards; most of them with cash and checks in them. On the Friday before Christmas, 2,000 pounds of mail arrived in Shallmar.

A week before Christmas, the Shallmar Relief Committee decided that since the town’s residents had been blessed by so much kindness that they would be just as generous. The committee sent out food and clothing to help another 70 families in the region who were in just as bad a shape as families in Shallmar had been. Some got money, some got clothing and they all got food.

“Today with $5,000 on deposit to their credit in a nearby bank, with tons of canned food piled up in their schoolhouse and more toys for their children than they know what to do with, the people of Shallmar have a realization of the Christmas message of “good will to men,” George Kennedy wrote in The Washington Star.

On the Friday before Christmas, the members of the Shallmar Relief Committee filled the school classrooms with the items that had been held back from distribution. Children were allowed into the school to select one toy, one novelty and one book. They were stunned at the abundance that confronted them and were hesitant to pick anything up. The girls, especially, were slow in selecting their dolls. They would look at the dolls without touching them and once their decision was made, they would pick up their doll and hug it.

Of all of the children who came to the toy shop that day, only one returned. Six-year-old Elaine Paugh came back about an hour after she had finished her selections. She quietly told Andrick that her mother had told her to return the very nice doll that she had selected for herself. She was obviously fighting back tears as she handed the doll to Andrick.

Andrick told her to go ahead and select another doll, but he knew something that Elaine didn’t. Her mother had picked out a beautiful doll for her on Friday evening and thought that another little girl should get the nice doll that Elaine had picked out. Elaine would be sad for only a day.

That evening, Paul dressed up as Santa Claus and delivered bags of candy, nuts and oranges to each of the families in Shallmar.

Charlotte Crouse and her brother were fighting that evening and too excited about the coming of Christmas to go to bed. Her mother finally had enough and told them, “If you don’t stop fighting, Santa Claus won’t come.”

At that moment, Charlotte looked up and saw Andrick outside the window in the living room. Of course, she thought she was seeing Santa Claus. She quickly stopped fighting with her brother and was on her best behavior for the rest of the night.

The next morning Charlotte got the doll for Christmas that her parents had picked out for her.

At Christmas morning church services, preachers announced that children from surrounding towns would be welcome to come and pick out their own toys at the Shallmar School. The relief committee had decided that it wanted to make sure that all of the gifts were shared with other children who might not have a Christmas otherwise.

Donations to Shallmar and its residents continued flowing into town even after Christmas. With hunger only temporarily eased by what grew to an estimated $7,000 in cash and $30,000 in food, toys, clothing and other items by early 1950, Andrick and the Shallmar Relief Committee turned their attention to long-term solutions for the town’s problems. The money lasted until the account was closed in May1952.