On October 27, 1874, John Resley, son of the clerk of the circuit court of Allegany County, shot and killed Lloyd Clary, the editor of the Cumberland Daily Times and a Confederate Civil War hero. It appeared to be an open-and-shut case. After all, Resley had confessed to the shooting.

However, just as a battle plan becomes obsolete as soon as the enemy is engaged, so too, go jury trials once the judge calls the court to order.

Resley’s murder trial began on January 29, 1874, barely three months after the murder.

The importance of the case became clear when Maryland Governor William Pinkney Whyte sent the state’s attorney general Andrew Syester to assist Allegany County State’s Attorney William Reed with the prosecution.

The defense had four lawyers. Col. Charles Marshall of Baltimore was the lead attorney and James M. Schley, J. J. McHenry and William Price, all of the Cumberland bar were assisting.

Chief Justice Alvey, Associate Justice Motter, and Associate Justice Pearre presided over the trial.

Reed gave the opening statement for the prosecution at the trial saying “they would prove, he thought, that Resley had not read the article when he committed the act,” according to the Hagerstown Mail.

However, the most damning piece of evidence Reed said would be that Resley had confessed in front of witnesses. While standing on Baltimore Street, Resley said, “Nobody else would do it and I did it.”

What Reed was starting to do was lay out a case of premeditated murder based not on a newspaper article, but on Resley’s hatred for Clary.

Schley deferred giving an opening statement to the jury until the state had made its case.

Among the witnesses called was another Cumberland Daily Times editor named Thomas McCardle. On hearing shots fired, McCardle has rushed down from the pressroom and seen Clary holding his throat. “He leaned against the wall as if completely exhausted, his body trembling as if from the effort to keep his feet, holding his throat by one hand, and with the other arm hanging down, holding a pistol in that hand,” the newspaper reported.

McCardle testified that he had never seen Resley with a pistol before then. The defense went further to suggest that Clary could have seen Resley coming from a window and gone to get the gun.

Clary had said in his statement he had been shot without being given a chance and he said as much to Resley just before the man shot him the second time. Clary said he hadn’t been able to get his pistol out to return fire.

Schley presented conflicting testimony that Clary had drawn his pistol and furthermore medical evidence showed that Clary wouldn’t have been able to say anything immediately after being shot in the throat as Clary said in his own statement.

A later witness would testify that Clary had hurried him out of his office just before rushing out to meet Resley on the stairs. This same witness had heard Clary and Resley argue, Clary’s pistol misfire and then two shots from Resley. Resley hadn’t gone to the office seeking to kill Clary. Resley had shot him in self-defense.

Other witnesses testified that Clary had hated Resley and said, “if ever he crossed his path again he would fill him as full of holes as a net,” the newspaper summarized Clary saying about Resley at one time.

After two days of testimony, the jury retired for six hours before returning a verdict of not guilty.

“Resley was then escorted home by the crowd, cheering all the way,” the New York Times reported.

Resley would live to be 73 years old and die from a stroke in January 1916.

You might also enjoy these posts:

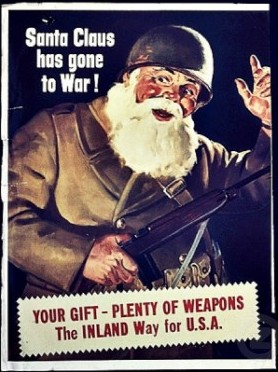

The “date which will live in infamy” cast a large, dark shadow over Christmas 1941 in Allegany County.

The “date which will live in infamy” cast a large, dark shadow over Christmas 1941 in Allegany County.

It’s been a long time coming, but

It’s been a long time coming, but  Matt Ansaro returns to his hometown of Eckhart Mines in the Western Maryland coal fields. It has been five years since Matt was here, and he swore when he left in 1917 that he would never return. Although Matt’s parents are dead, the rest of his family welcomes him home with open arms.

Matt Ansaro returns to his hometown of Eckhart Mines in the Western Maryland coal fields. It has been five years since Matt was here, and he swore when he left in 1917 that he would never return. Although Matt’s parents are dead, the rest of his family welcomes him home with open arms.