They say, “The pen is mightier than the sword” and for Lloyd Clary that indeed proved true. The young newspaper editor of the Cumberland Daily Times had survived the bullets and swords of the Civil War only to be felled because of something he wrote on October 27, 1873.

“Never in our experience have we been called upon to publish the details of an occurrence more truly painful and shocking than that of the killing of Lloyd Lowndes Clary, the brave editor of the Cumberland Daily Times by John H. Resley…” the Hagerstown Mail reported after the murder.

It was in the offices of the newspaper on Oct. 27 that John Resley shot Clary twice, once in the neck and once in the body. The neck shot would kill Clary later that evening.

Though Resley left the scene of his crime, he did not flee. He walked across Baltimore Street and stood on the opposite side looking at the newspaper office. “A considerable crowd gathered around Mr. Resley while be stood on the street. He was very pale and much excited, and moved about nervously. He did not seem inclined to converse, and several times rebuffed persons who spoke to him,” reported the Hagerstown Mail.

Eventually, Cumberland Police Officer Magruder saw Resley and approached him.

“Am I wanted?” Resley asked.

“Yes you are,” Magruder told him and arrested him.

Resley was later indicted for Clary’s murder.

While the newspapers detested Resley’s actions, they seemed to understand the reasons behind it. The Hagerstown Herald and Torch noted, “It is a fact that the editor referred to wielded a caustic pen, and his paper, as long as we received and read it, contained some terribly severe articles against political opponents.”

As with many men of his time, Clary had not been afraid of a fight. He was a Confederate veteran of the Civil War. “Mr. Clary was intensely Southern in his feelings, every pulsation of his young heart beating in unison with the late struggle of the seceding States for their guaranteed and Constitutional rights,” one obituary noted.

He had joined McNeill’s Rangers in 1862. The Hagerstown Mail credits Clary for planning and executing the kidnapping of Union Generals George Crook and Benjamin Kelley from a hotel on Baltimore Street in February 1865.

“Young Clary in company with four others, captured the Federal pickets, dashed into Cumberland and at three o’clock in the morning surprised Generals Crook and Kelley, and brought them safely out,” the newspaper reported.

Both generals were taken to Richmond where they were paroled and exchanged for Confederate Brigadier General Isaac Trimble.

Crook would later say, “Gentlemen, this is the most brilliant exploit of the war!”

After the war, Clary was a reporter and then editor of the Mountain City Times, which merged with the Cumberland Times and Civilian to become the Cumberland Daily Times in May 1872.

“From its first note to its last the Times has not uttered one uncertain sound. It had but one voice—that of condemnation and exclusion from office of the men whom it had convinced of betrayal of their trusts. Thus fighting he fell with his harness on, a martyr to the cause of honesty, truth and Justice,” the Cumberland Daily Times noted in its obituary of Clary.

Though there was no question in anyone’s mind that Resley had killed Clary, there were still unanswered questions that would come to light during the trial that changed how everyone looked at the murder.

You might also enjoy these posts:

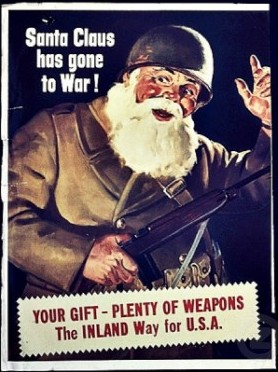

The “date which will live in infamy” cast a large, dark shadow over Christmas 1941 in Allegany County.

The “date which will live in infamy” cast a large, dark shadow over Christmas 1941 in Allegany County. Burning coal was once a common way to heat homes in Pennsylvania, at least as far back as the mid-1700s when bituminous coal was first mined at “Coal Hill”, which was across the Monongahela River from Pittsburgh. However, in York, many residents apparently feared the burning rock, according to the York Dispatch.

Burning coal was once a common way to heat homes in Pennsylvania, at least as far back as the mid-1700s when bituminous coal was first mined at “Coal Hill”, which was across the Monongahela River from Pittsburgh. However, in York, many residents apparently feared the burning rock, according to the York Dispatch.

An umbrella, the inexpensive shield from the rain, was once considered too feminine for men to use.

An umbrella, the inexpensive shield from the rain, was once considered too feminine for men to use.

Tromping through the heavy snow was not too hard for the large horse even as it pulled the dairy wagon along behind it. Emigsville Dairy Company was determined to see that its customers got fresh milk and cream, despite the fact that the storm had shut down just about everything in York.

Tromping through the heavy snow was not too hard for the large horse even as it pulled the dairy wagon along behind it. Emigsville Dairy Company was determined to see that its customers got fresh milk and cream, despite the fact that the storm had shut down just about everything in York. The charter for a railroad in Adams County, Pennsylvania, was approved on February 18, 1836. The surveying of a route over the mountains and south into Maryland began. Gettysburg lawyer Thaddeus Steven’s less-than-transparent methods earned him lots of critics who were quick to point out that the Gettysburg Extension of the Pennsylvania Main Line did more to make contractors rich, create unnecessary jobs, and buy votes than it did to create a viable rail line.

The charter for a railroad in Adams County, Pennsylvania, was approved on February 18, 1836. The surveying of a route over the mountains and south into Maryland began. Gettysburg lawyer Thaddeus Steven’s less-than-transparent methods earned him lots of critics who were quick to point out that the Gettysburg Extension of the Pennsylvania Main Line did more to make contractors rich, create unnecessary jobs, and buy votes than it did to create a viable rail line. Where 19th Street ends in Windber is where a frightening, fascinating journey begins.

Where 19th Street ends in Windber is where a frightening, fascinating journey begins.

Trolley attraction

Trolley attraction

Too Much Government Spending Forces Fiscal Change

Too Much Government Spending Forces Fiscal Change